Emotion's not just the name of a chip

Some people think they can just bandy about the word as a marketing ploy

Emotion is, well, rather an emotional word. That's why it shows up so often in video games. It's a selling point. It's a great way to describe a thing that has no description. Especially when you're trying to describe a concept that other people don't otherwise understand.

Take video games, for instance. You don't have to describe what a video game means to other video game players. They already know. Just say the words "video game" and an entire world of possibilities opens up in their minds.

But for people who don't understand video games? It's a harder concept. For them, why would anyone waste hours of their day, day after day, trying to beat a never-relenting, artificial opponent and then come back time and again for the same treatment? The single word that gets the concept to be understood by those standing outside the video game-playing box is "emotion."

So that's the word that they use in order to market video games to those outside of the world of video game making. You see it over and over again.

Let's go back to 1999 when Sony was first trying to market the Playstation 2. It would contain no ordinary CPU -- it would contain the "Emotion chip."

They undoubtedly stole the name from Star Trek: The Next Generation. In the series, the android character Data was equipped with an "Emotion chip" in order to turn his Pinocchio-like character into more of a little boy.

Ars Technica explained it this way: "The Emotion Engine consists of eight separate "units", each performing a specific task, integrated onto the same die. These units are: a CPU core, two Vector Processing Units (VPU), a 10 channel DMA unit, a memory controller and an Image Processing Unit (IPU). There are three interfaces: an input output interface to the I/O processor, a graphics interface (GIF) to the graphics synthesizer and a memory interface to the system memory."

Pretty dry stuff, eh? That's why they called it an "Emotion chip." The name itself evokes something beyond the mere description of the object. It also infers how people will feel when they use the thing.

I mean, really, didn't you get emotional when you played those games on the PS2? You must have. You certainly bought enough of the things. And if you want to sell something, you've got to call it something.

And you've got to call it something good.

Back in the 1960s, Nissan was developing a new car for sale in Japan. The head of Nissan loved a certain American movie: "My Fair Lady." He decided to name the car after the movie and gave it the name of "Fairlady." They sold it with that name in Japan. But when they decided to try to sell it in America, the name "Fairlady" just wasn't going to be the right name for a small, two-seat sports car to compete with Chevy's Corvette or Ford's Mustang. So they renamed it for America, by using the designation of the engine block of the car: 240Z.

The 240Z turned out to be a huge financial success for Nissan, and the car still exists today, upgraded over the years to 370Z. But imagine if it had been named "Fairlady" in America. What would that name had evoked? And would it have been such a big seller?

So video game marketers always fall back on "Emotion" when trying to sell video game concepts to nonbelievers. And this is happening again. Only this time they're using science.

A company called Affective is trying to sell the notion that they can measure the emotional responses of video game players, that those responses can generate data that can be of value in determining the serviceability and salability of those games.

The company purports to determine a person's emotions by measuring their facial expressions when watching someone on TV and delivering the data in a graphic representation, alongside a filmstrip of the images the person was viewing at the time.

Of course, this in itself is a bit of a disingenuous notion: a person's facial reactions are not a true indication of their inner feelings of emotion. That can be proven by a simple viewing of a "Try Not To Laugh" challenge video on YouTube's React channel. The people who win the challenge often admit they found something funny, but never showed the reaction on their faces.

Affective claims, "Now it is possible to respond to the emotional state of a user just by accessing the all pervasive webcams attached to our devices." They even let me try out their software by displaying some recent funny ads and let me view the graph of your reactions to them.

So, I'm game. I took their little challenge and "reacted" to five TV ads while their software viewed me from my computer's web cam. Since I'd be good at the "Try Not To Laugh" challenge, anyone looking at my graph at Affective would probably think I am dead. After looking at two funny Doritos ads, a poignant Budweiser dog-and-Clydesdales ad, an M&Ms ad and a Muppets ad for Toyota, I barely showed up in their graph.

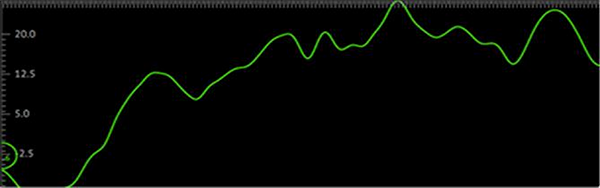

According to Affective, this is a sample of an "Aggregate chart of emotion tracked over time using the Affdex emotion sensing SDK." It just looks like a squiggly line to me.

Yet Affective makes the claim that their "industry leading emotion sensing technology is poised to transform how we develop and play games. By measuring facial expressions of emotion, we understand what players are feeling. This allows game developers to create adaptive games which can dynamically respond to and record player emotion."

I've watched people play a lot of video games. Some people show a lot of emotion while they're playing. I'll bet that Markiplier guy who does those game-playing videos on YouTube would have numbers that flew off Affective's charts. But he's on TV. He gets his notoriety by being ultra-emotional while playing.

I've also watched NinJaSistah play games: She's intense and studious. She'll occasionally burst out with an obscenity while playing, but then it's back to work while she's grinding it out on the streets of New York City in The Division (You can't show too much emotion in Manhattan -- you'll get mugged).

So I don't buy Affective's notion that "game developers now have a tool at their disposal that can read a player’s emotional state [in] real time during gameplay..." People's faces just aren't a reliable window to their true, inner emotions.